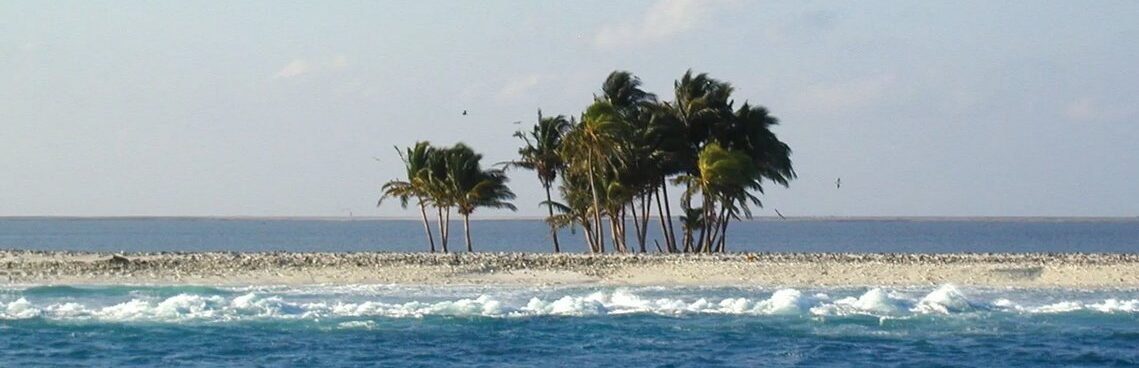

Clipperton Island, uninhabited French island in the eastern Pacific Ocean, 1,800 miles (2,900 km) west of Panama and 1,300 miles (2,090 km) southwest of Mexico. It is a roughly circular coral atoll (2 square miles [5 square km]), barely 10 feet (3 m) high in most places but with a promontory 70 feet (21 m) high surmounted by a ruined 19th-century lighthouse. Vegetation consists of low scrub, patches of wild tobacco, and a few coconut groves. Named after the English mutineer and pirate John Clipperton, who made the island his lair in 1705, it was listed as a U.S. island under the Guano Act (1856) but had already been annexed by France in 1855. Seized by Mexican forces, it was garrisoned from 1897 to 1917. With the opening of the Panama Canal, Clipperton Island attained new importance. In 1930 King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy arbitrated the conflicting claims in favour of France. It was administered from French Polynesia until 2007, when France assumed direct administration of the dependency, placing it under the authority of the Minister of Overseas France.

On one of the most remote tropical islands on Earth, a million ravenous crabs share a thin ring of dry land with tens of thousands of birds, 2,000 invasive rats, the rusting remains of a guano industry, and the occasional adventurous visitor.

Located 1,120 kilometers southwest of Mexico, French-administered Clipperton Island is the only atoll in the tropical eastern Pacific. It’s named for English pirate John Clipperton, who’s said to have used it as a hideout in the early 18th century. Later, the island proved to be inhospitable during attempts to establish guano mining operations and small settlements there, and it remains uninhabited today.

An extraordinary feature of the island is its biologically significant interior lagoon, which has no outlet to the sea. Characterized by a strong vertical salinity gradient (the water at the top is nearly fresh), the lagoon is rich in nutrients and supports an abundance of plant life, including extensive seagrass beds covering 45 percent of its surface.

THE MISSION

For their expedition to Clipperton, conducted in partnership with the University of French Polynesia, the Pristine Seas team packed an impressive array of state-of-the-art tools and equipment. Among the items on their checklist: dive and camera gear, drop cameras, pelagic cameras, underwater video stations, science sampling kits, shark and tuna tagging gear—and a three-person submarine.

Traveling a thousand kilometers from the coast of Mexico, they set out to better understand the island’s reefs, unexplored deep waters, and surrounding seamounts. After 140 scuba dives, 14 submarine dives, 58 remote camera deployments, a five-day land survey, and a two-day snorkeling study of the lagoon algae, the team achieved a comprehensive assessment of the ecosystem.

Clipperton’s waters, they found, are teeming with life. A high degree of coral cover, a strong population of sharks, exceedingly brave moray eels, and an abundance of endemic fishes all indicate a vibrant ecosystem. Yet even at this far-flung outpost, free of human activity for a century, the team noted clear evidence of fishing pressure, including a large number of fishing lines and disproportionately juvenile sharks.

THE RESULT

THE HIGHLIGHTS

Aboard the Argo, the team can smell Clipperton from miles away. Silky sharks accompany the descending sub. Moray eels get wrapped up in the excitement—and develop a taste for ears and fingers. It takes four days for thousands of birds to turn a blue tent white. The island proves to be at a turning point.